What is ENSO? Page 2 - SSTs and trade winds

This is Page 2 of the sub-series "What is ENSO?". If you haven't already, please read Page 1 first. For convenience, keep that page open in a different tab.

= = =

What is ENSO?

In the previous post, we learnt to identify ENSO phases from the perspective of sea surface temperature anomalies. In this post, I'm going to answer a question that no one really asked ― What if I wanted to identify ENSO phases from the perspective of sea surface temperatures (SSTs) instead? What if, for no good reason but because I felt like it, I wanted to do away with the "anomalies" bit?

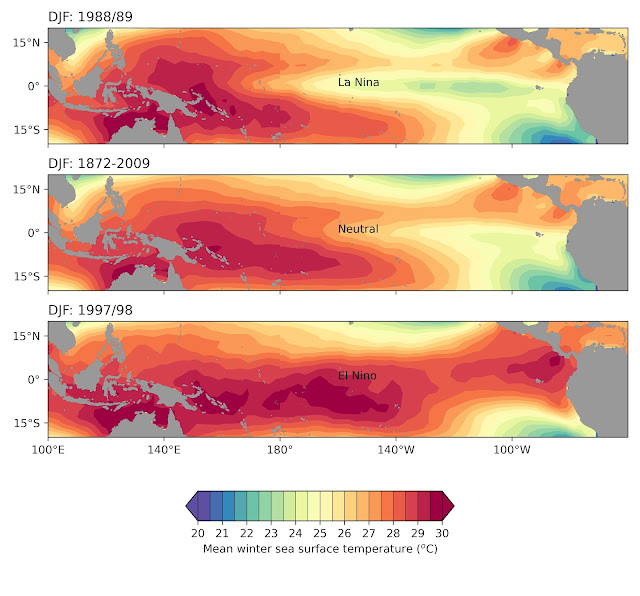

Looking at SSTs instead of SST anomalies makes matters unnecessarily complicated, but we're going to do it anyway because it also teaches us a lot. In the image below, I've plotted SSTs from the HadISST dataset. These are mean SSTs for the months of December, January and February (DJF) over all years from 1872-2009.

Why did we select the months of DJF? Because ENSO events can be seen most clearly during these months. It does not mean that they "occur" during these months or are restricted to these months. In fact, they take several months to develop before being seen most clearly during DJF.

The plot above shows an interesting pattern of SSTs in the Pacifc, with warmer surface waters on the west and cooler surface waters on the east. Scientists call these patterns the "Warm Pool" and the "Cold Tongue" respectively. Different ENSO events tend to affect these SST patterns differently.

In the image below, I've plotted the La Niña event of 1988 and the El Niño event of 1997 (you may remember that we referred to these events in the previous post too), with the "neutral" conditions in between (which is the same as the plot above).

We can now begin to see what happens to absolute SSTs (instead of anomalies) during ENSO events. During the La Niña, the Cold Tongue seemed to expand westwards at the expense of the Warm Pool. The opposite happened during the El Niño. But these plots are complicated ― and the reader's perception is often influenced by what color scheme was used to plot them. The SST anomalies from the previous page showed a much clearer ENSO signal.

= = =

Why do the Warm Pool and the Cold Tongue exist?

The primary control over the temperature of any place is its latitude ― this determines the amount of sunlight it receives, and hence broadly dictates how warm/cool the place would be. The latitude is not the only control, but it is an important one. So why do waters in the Pacific Ocean show such different temperatures in the west and the east, even when they are at the same latitude? (Don't worry, we are not digressing ― this is actually an important piece of the ENSO puzzle!)

To answer this question, we need to know a little bit about wind patterns. In the equatorial region, winds near the surface of the Pacific Ocean flow from east to west. For this reason, they are called the easterlies. They are also called the trade winds, since this reliable wind pattern has helped trade ships since historical times.

The trade winds tend to push surface waters from the eastern side of the ocean to the western side, actually leading to a measurable difference in sea surface heights in the two regions! When waters from the eastern boundary of the ocean are pushed away at the surface, deeper waters come up to replace them. The formal term for this is upwelling (but we needn't go too deep into this just yet ^^). Thus, the persistent easterly pattern of the surface winds leads to this SST pattern where the eastern part of the basin has cooler-than-western waters at the surface, primarily because they are being constantly moved towards the west and replaced by the cooler-than-surface waters from the depths. We can now begin to apprehend a relationship between the strength of these trade winds and the peculiar patterns of the SSTs.

In the previous post, I wrote: "To me, the first and foremost thing to know about ENSO is that 一 if it's an El Niño event, the equatorial Pacific is hotter-than-average; if it's a La Niña event, the equatorial Pacific is cooler-than-average; and if the equatorial Pacific looks the same as the average, there are neutral conditions." Referring to the simplified image below, we can now move on to the second thing to know 一 La Niña events are accompanied by stronger-than-normal trade winds, which lead to more upwelling of cooler waters, whereas El Niño events are accompanied by weaker-than-normal trade winds which lead to less upwelling of cooler waters.

So far, we talked about wind patterns and SSTs. Trouble brews when we start talking about wind anomalies and SST anomalies, which is what several science communication pieces and scientific journal articles do. Looking at the image above, it is clear that La Niña events (associated with stronger-than-normal easterlies) are accompanied by easterly wind anomalies. That is, if we were to look at the La Niña winds minus Neutral winds, the resultant anomalies would also be easterly. On the other hand, El Niño events (associated with weaker-than-normal easterlies) are associated with westerly wind anomalies. That is, if we were too look at El Niño winds minus Neutral winds, the resultant anomalies would be westerly. This is also shown in the simplified image below with the arrows showing wind anomalies and the colors showing SST anomalies.

| Image adapted from: Source |

To me, this is what makes many ENSO discussions difficult to follow. Scientists tend to weave in and out of discussions of SST/SST anomalies and wind/wind anomalies, which can sometimes lead to misunderstandings. In the next post, I will introduce pressure/pressure anomalies too 一 but hopefully a clear picture is emerging, and adding a further layer to this discussion won't be quite so bad.

= = =

If you like such posts, you may subscribe here for email alerts.

Comments

Post a Comment