Climate Change: The Fundamentals - Part III

What does the future look like?

While trying to understand the climate crisis, it is natural to ask - "What's going to happen and how do we plan for it?"

A "prediction" of the future is necessary to determine national policies. Each country or community has its own set of constraints, such as finite resources and other unsolved problems that compete for priority. Hence, often, instead of asking "How can we make it better?" we are forced to ask "How can we make it less worse?"

How do experts answer questions about the future? Naturally, their answers depend on a lot of factors. While the basic science is based on well-understood laws of nature, the human touch makes matter very complicated. Simply put, how the climate affects us depends on how we affect the climate in the first place.

The greatest uncertainty associated with determining our future emissions is us - what choices will we make economically, politically, ideologically, and of course what technological advances will we see incoming years. We are the hardest part of the equation to predict!— Prof. Katharine Hayhoe (@KHayhoe) December 1, 2018

There is a vast amount of scientific literature that discusses future climate scenarios. I encourage the reader to go through IPCC reports, which are a compilation of the best existing knowledge regarding the climate crisis. I discuss scenarios only from the last IPCC report, though it was released in 2013 and there have been developments since then. I do this because

(a) there is enough to be learnt from the 7 year old report too,

(b) policy hasn't exactly caught up with that either.

(a) there is enough to be learnt from the 7 year old report too,

(b) policy hasn't exactly caught up with that either.

Climate model projections - how experts speak about the future

First, let's bust a few popular myths about future scenarios and policy suggestions.

Experts do not give "doomsday predictions"

Future projections depend on specific conditions fed into the climate models. Every analysis mentions physical principles, input data, caveats, probabilities and uncertainties. To put it bluntly, experts do not "predict" the future like a babaji. As for climate scientists or activists being called "alarmists", my standard reply is based on the actual meaning of the word "alarmist".

Common sense dictates that when the diagnosis is alarming, it helps to not make a villain out of the doctor, but to have a constructive discussion about how things could be improved. If you care, that is.

I'm getting a bit sick of climate scientists being called 'alarmists'.— Shivangi Tiwari (@shivangi__t) January 10, 2020

So the next time your mother gets sick and the doctor gives you an 'alarming' diagnosis, call him an 'alarmist', throw a fit, and walk out of the hospital.

For those who don't get 'alarming' vs 'alarmist'.

Common sense dictates that when the diagnosis is alarming, it helps to not make a villain out of the doctor, but to have a constructive discussion about how things could be improved. If you care, that is.

Policy suggestions do not come from the scientists alone

I was once told "the world is not a lab simulation" and scientists are not capable of dictating policy matters. That's actually true, which is why the IPCC reports are written not just by scientists but also by experts in engineering, social sciences, economics and ethics. The climate crisis requires an interdisciplinary approach, and the IPCC understands this.

"Climate models are unreliable" -- 👀

If I had a paisa for every time this line was mis-used to delay climate action, we could have a dedicated climate fund by now. The models used by the IPCC are developed by competent experts, and they are critically analysed so that they keep improving (example). Climate models aren't perfect, but they're reliable. Brief snapshot here, take a look yourself.

More details in this article by Carbon Brief. If you're interested, you can also check out this paper in Geophysical Research Letters, covered here on NASA's climate website too.

Please note that anyone who has improvements to suggest for the IPCC's methodology is welcome to contribute to the process -- link here. My personal experience has been rather unfortunate in this regard. The majority of the people who criticised climate models seemed to have little idea about even the basic principles behind climate modelling. Constructive criticism is difficult to find; and there is ample mud-slinging from people with vested interests.

Please note that anyone who has improvements to suggest for the IPCC's methodology is welcome to contribute to the process -- link here. My personal experience has been rather unfortunate in this regard. The majority of the people who criticised climate models seemed to have little idea about even the basic principles behind climate modelling. Constructive criticism is difficult to find; and there is ample mud-slinging from people with vested interests.

Future Climate Change Scenarios

The IPCC's method of describing future scenarios has gone through an evolution from 1992 to 2013.

The IPCC currently uses the term Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) to describe 4 specific future scenarios.

The term "Concentration Pathways" distinguishes this approach from the previous approach of "Emission Scenarios". Simply put, the future is now thought of not just in terms of the Green House Gas (GHG) emissions but in terms of GHG concentrations. Why? Because GHG concentrations in the atmosphere do not depend only on how much GHGs we emit, but also on land-use changes. Thus this new approach is more comprehensive than the last one.

Each RCP has a number attached to it which indicates the change in radiative forcing (≈ extra energy trapped) by the year 2100, compared to pre-industrial levels. Thus, a lower number indicates a better scenario for the future than a higher number.

For a baseline:

The 4 specific scenarios described are:

RCP 2.6

This future pathway describes a "very low forcing level" where the radiative forcing is about 2.6 W/m2 by the year 2100. In terms of carbon concentrations, this RCP would result in ~ 490 ppm CO2 equivalent by the year 2100. Note that this does not mean that the radiative forcing will peak at 2.6 W/m2 The RCP 2.6 visualises a peak in radiative forcing of about 3 W/m2 which would then be lowered to 2.6 by the end of the century. This would require strong climate action and significant reductions to carbon emissions.

RCP 4.5

This represents a "medium stabilization scenario" with ~4.5 W/m2 radiative forcing and ~650 ppm CO2 equivalent by the year 2100.

RCP 6.0

This also represents a "medium stabilization scenario" but with a higher radiative forcing of 6 W/m2 and ~850 ppm CO2 equivalent by the year 2100.

RCP 8.5

This represents a "very high baseline emission scenario" with 8.5 W/m2 of radiative forcing and ~1370 ppm CO2 equivalent by the year 2100.

The IPCC currently uses the term Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) to describe 4 specific future scenarios.

The term "Concentration Pathways" distinguishes this approach from the previous approach of "Emission Scenarios". Simply put, the future is now thought of not just in terms of the Green House Gas (GHG) emissions but in terms of GHG concentrations. Why? Because GHG concentrations in the atmosphere do not depend only on how much GHGs we emit, but also on land-use changes. Thus this new approach is more comprehensive than the last one.

Each RCP has a number attached to it which indicates the change in radiative forcing (≈ extra energy trapped) by the year 2100, compared to pre-industrial levels. Thus, a lower number indicates a better scenario for the future than a higher number.

For a baseline:

|

| Source |

The 4 specific scenarios described are:

RCP 2.6

This future pathway describes a "very low forcing level" where the radiative forcing is about 2.6 W/m2 by the year 2100. In terms of carbon concentrations, this RCP would result in ~ 490 ppm CO2 equivalent by the year 2100. Note that this does not mean that the radiative forcing will peak at 2.6 W/m2 The RCP 2.6 visualises a peak in radiative forcing of about 3 W/m2 which would then be lowered to 2.6 by the end of the century. This would require strong climate action and significant reductions to carbon emissions.

RCP 4.5

This represents a "medium stabilization scenario" with ~4.5 W/m2 radiative forcing and ~650 ppm CO2 equivalent by the year 2100.

RCP 6.0

This also represents a "medium stabilization scenario" but with a higher radiative forcing of 6 W/m2 and ~850 ppm CO2 equivalent by the year 2100.

RCP 8.5

This represents a "very high baseline emission scenario" with 8.5 W/m2 of radiative forcing and ~1370 ppm CO2 equivalent by the year 2100.

So what does all this mean practically?

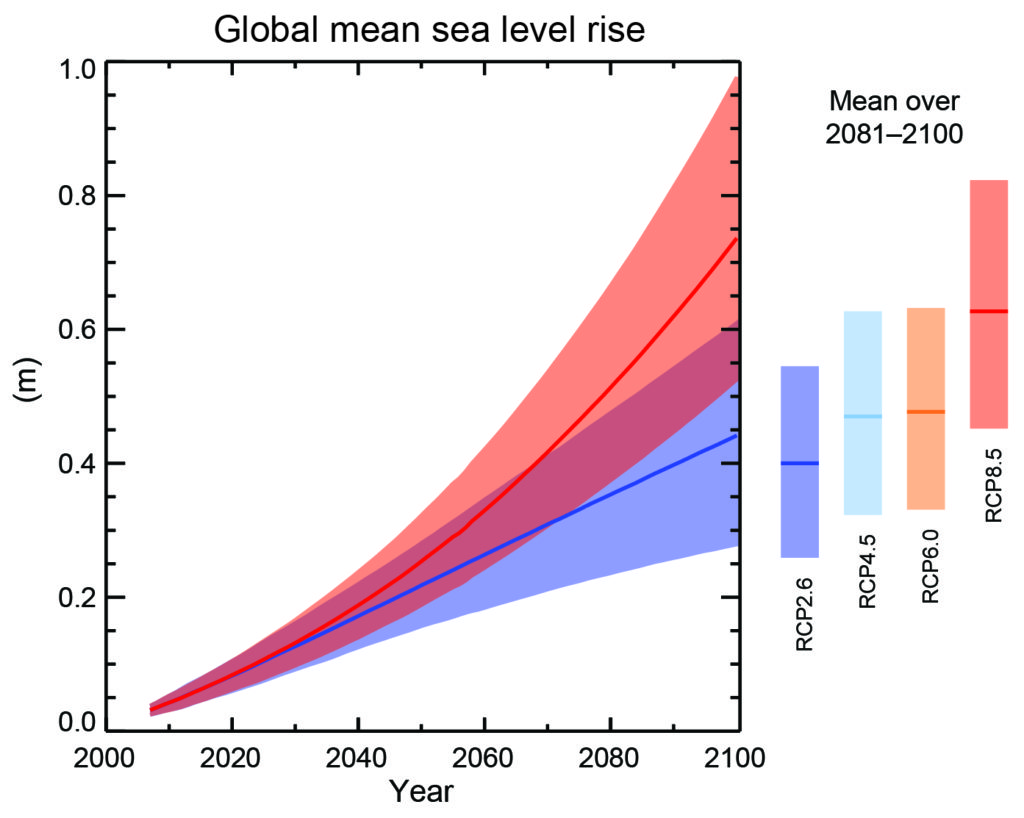

The IPCC report of 2013 projected an increase of ~4 deg C and ~0.7 m rise in global mean sea level for the year 2100 for the RCP 8.5 scenario. For the RCP 2.6 scenario, an increase of ~1 deg C and ~0.4 m rise in global mean sea level is expected.

|

| Source |

|

| Source |

A very pertinent result of modelling these RCPs is also shown here. The graph shows how GDP is expected to evolve in the 4 scenarios.

|

| Source: van Vuuren et al. (2011) |

One can't distinguish very well between the different pathways till at least the year 2020. But in the long-term, it is quite clear which pathway is more beneficial for "development". The RCP8.5 which does not *impede economic growth* with climate concerns actually leads to a lot more damage and reduced GDP growth.

The RCPs were originally described by van Vuuren et al. (2011). The paper also highlights the limitations of the RCPs as in the year 2011 (when the paper was published), and how they are not supposed to be used.

In the next IPCC report, the RCPs will be complemented by the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs). But more about that in a later post.

Which RCP will likely occur?

First, no likelihood was indicated for any of the RCPs. This means that experts only gave forecasts for specific paths the future could take, but do not place any bets on which one is most likely to occur. The course of the future depends on too many things, and most importantly on policy decisions that reduce emissions. We're likely hanging somewhere between RCP4.5 and RCP6. A more technical comment at this question is available here.

In terms of temperature, it is highly unlikely that we will limit warming to 1.5 deg C but we may have a fighting chance of limiting it to a 2 deg C rise. Many experts opine that we're looking at a 3 deg rise; I personally agree. The next IPCC report, to be released in 2022, would shed greater light on this.

▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁

Points to ponder:

- What would an RCP2.6 and an RCP8.5 mean for your country and region? For starters, think in terms of temperature, sea level.

- What transformations are indicated for the next 10, 20 or 30 years?

- What socioeconomic pathways do you think go most in-hand with good climate policies? For starters, think in terms of population and "development".

▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁

Comments

Post a Comment