IPCC First Assessment - What we can learn from a 30 year old report

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was established in 1988. It produced its First Assessment Report (FAR) in 1990. 3 decades later, much remains to be learnt from this superannuated report.

To remind the reader, in the last 30 years we got computers, mobile phones, internet, smartphones and smart TVs. India saw 6 different Prime Ministers and 7 different Presidents in this time span. There were 8 ICC World Cups; India defeated Sri Lanka to win one of these. 1990 was 4 years before Andaz Apna Apna; in fact, it was the year when Sri Devi got an award for Chaalbaaz. Titanic was still 7 years away; The Matrix, 9. You may also look towards your own life to remember what the last 30 years meant, but I believe the point is quite clear -- 1990 was a long, long time ago.

In this 3-part series (one for each Working Group), I take a very cursory look at the First Assessment Report (FAR). The aim is not to delve into technical details, for which I hope you will explore the original reports available on the IPCC website. The aim, instead, is to try to position ourselves in 1990, understand where we stood back then and hence, try to understand how far we've come.

Working Group I (Science)

Back in 1990, the IPCC informed the governments all over the world about some gases that were enhancing the natural greenhouse effect.

We have now added a few gases to this list (notably, Ozone -- whose effect the FAR did mention but could not quantify -- and Sulfur Hexafluoride), but these 4 gases remain among top concerns even today. Thus, the main culprits for climate change were known 30 years ago.

Feedbacks

It was also pointed out that global warming would increase the concentration of water vapour (also a greenhouse gas) in the atmosphere. Thus, the concept of feedbacks was introduced. To put it simply, a feedback is something that both affects and is affected by a process. In this case, it's a positive feedback -- warming leads to more water vapour, and more water vapour leads to even more warming. It was pointed out that climate models which are used to make "predictions" about the future do not take into account all known feedbacks. (This is true today as well. As our understanding of feedbacks grows, we also face fresh challenges for their incorporation into climate models. Climate models are, like most things being researched, a work in progress.)

This makes the whole situation more complicated and worrying. The FAR stated, "It appears that, as climate warms, these feedbacks will lead to an overall increase, rather than decrease, in natural greenhouse gas abundances. For this reason, climate change is likely to be greater than the estimates we have given." Thus, if climate modelling is to be taken with a pinch of salt, it is far wiser to take results as under-estimates rather than over-estimates.

The predictions

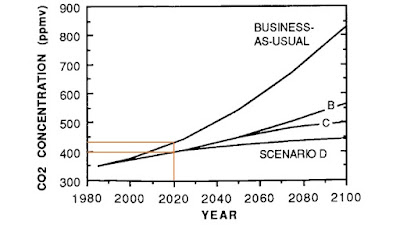

The FAR gave predictions under four modelling scenarios: A - D where A was also called "Business-as-usual". We can now compare what they predicted with what has happened since. Today, the CO2 concentration stands at ~412 ppm. This lies within the bracket estimated by the IPCC.

The temperature profiles turned out to be over-estimates. Today, the global mean temperature has risen around 1.2 ℃, which falls below the FAR's estimate for Scenario D (their most optimistic scenario) of almost 1.5 ℃. A happy mis-prediction, no doubt! What led to this over-estimation, how it improved climate modelling and how the improvements were incorporated in further IPCC reports would likely fill many blog posts.

A clear admission of uncertainties

The report clearly distinguished between what was known with certainty and what was estimated with what degree of confidence. The FAR stated, "The size of this warming is broadly consistent with predictions of climate models, but it is also of the same magnitude as natural climate variability. .. The unequivocal detection of the enhanced greenhouse effect from observations is not likely for a decade or more." Thus, the question -- "Man or nature?" -- was not answered back then. Perhaps this didn't make for a very strong cause for climate action back in 1990, but it adhered to scientific values. In the section "How much confidence do we have in our predictions?", the authors write, "..climate models are only as good as our understanding of the processes which they describe, and this is far from perfect. .. Nevertheless, for reasons given in the box overleaf, we have substantial confidence that models can predict at least the broad scale features of climate change."

It vexes me when climate deniers / sceptics try to undermine confidence in climate models by using the argument "climate models aren't perfect". First, nothing is perfect. As Gavin Schmidt puts it, if we had observations of the future, we would obviously prefer those! We use climate models because observations of the future are not available at this time. Thus, to put it simply, climate models are not perfect but they are (A) good enough and (B) the best we've got. But secondly, using this argument makes it seem as if scientists are claiming the models are perfect! That is quite far from the truth.

Another noteworthy admission was related to weather variability. The report says, "With the possible exception of an increase in the number of intense showers there is no clear evidence that weather variability will change in the future." Note the statement, the FAR states that there is no clear evidence -- thus, it could not comment on this aspect. Simply put, they did not know.

Comments

Post a Comment